China's digital yuan project, a blockchain-based cryptocurrency for consumer and commercial finance, can no longer be considered a pilot. That's the assessment by economic and cryptocurrency experts.

Those experts have been monitoring efforts in China and other countries developing and piloting central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) with the aim of establishing a blockchain-based virtual cash that is cheaper to use and faster to exchange, both at home and across international borders.

To date, the People's Bank of China has distributed the digital yuan, called e-CNY, to 15 of China's 23 provinces, and it has been used in more than 360 million transactions totaling north of 100 billion yuan, or$13.9 billion. The country has literally given away millions of dollars worth of digital yuan through lotteries, and its central bank has also participated in cross-border exchanges with several nations.

If e-CNY continues to be adopted and becomes the de facto standard for international commercial and retail payments, the privacy of those using digital currency, as well as the US dollar's days as the world's reserve currency, could be at risk.

Whatever nation figures out an internationally accepted financial transaction network for digital cash will be the one to set the standards around it, "and then everyone else will have to follow them," said Lou Steinberg, former Ameritrade CTO and managing partner at cybersecurity research firm CTM Insights. "Those standards will be designed with what the developer of them wants to accomplish. Surveillance could be built in.

"China wants digital cash because it's another tool to monitor citizen behavior - how much do you spend at the liquor store, do you go to the movies, and which ones?" Steinberg continued. "If all transactions are recorded and tied to your account, they know a lot. A similar concern about government monitoring exists in the US, though the motives for monitoring may differ from an authoritarian state."

The US has been considering creation of a digital representation of the dollar for nearly three years. In March, President Joseph R. Biden Jr. issued an executive order that, among other things, called for more urgency on research and development of a US CBDC, "should issuance be deemed in the national interest."

In November, the New York Federal Reserve Bank began developing a wholesale CDBC prototype. Named Project Cedar, the CBDC program hammered out a blockchain-based framework expected to become a pilot in a multi-national payments or settlement system. The project, now entering phase 2, is a joint experiment with the Monetary Authority of Singapore to explore questions around the interoperability of the distributed ledger.

"I don't think we're treating this like a Moonshot," Steinberg said. "The Fed's not saying this is the future, like it or not, and we need to have a say in how it unfolds, and therefore it becomes the most important thing we do."

The blockchain technology that underpins digital cash projects is the same as that used for Bitcoin and Ethereum cryptocurrencies. The difference is that CBDCs, like traditional cash, are backed by a central bank's authority, which is why they're called central bank digital currencies.

Distinct from online retail payments, such as those made via a mobile device, wholesale cross-border payments are transactions between central banks, private sector banks, and corporations. Cross-border spot trades (or immediate payments) are among the most common wholesale payments, as they are often required to support broader transactions, such as for international trade or foreign asset investment.

While the US has made some advances toward creating a CBDC, it still lags far behind other nations.

For example, Project Dunbarbrings together the Reserve Bank of Australia, Bank Negara Malaysia, Monetary Authority of Singapore, and South African Reserve Bank with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Innovation Hub to test the use of CBDCs for international settlements.

"We're looking at 13 current wholesale projects with different arrangements between countries," said Christian Catalini, the founder of the Cryptoeconomics Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). "The United States is clearly behind. Part of that is because there's not a consensus that a CBDC is needed or useful. There's only one clear nation leading the effort when it comes to both the scale of its experiment and its progress to date, and it is China."

E-CNY is a digitized version of China's cash and coins and, like other CBDCs, it was deployed on a blockchain distributed ledger - an online, distributed database that tracks transactions. That database uses encryption to ensure online cash and coins exchanged through it are tamper-proof, meaning only users with access to specific private-public keys can participate in the transaction. In real terms, for retail that could look like a QR code on a smartphone being used to make a purchase in a store. Or it could be a corporation transmitting a public key code that allows for a specific monetary exchange.

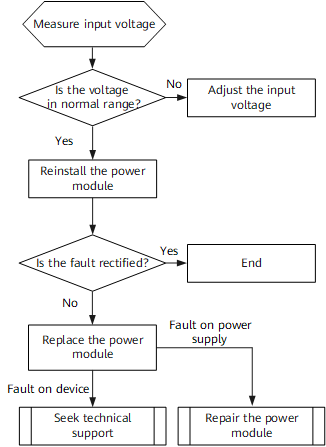

In 2020, the Atlantic Council, a Washington DC-based think tank, began tracking 35 CBDC projects. Today, it's watching 114 CBDC projects globally, measuring their progress based on four stages: research, development, pilot, and launch. China's e-CNY currency has been in the pilot stage since 2020, when it announced the digital currency at the Beijing Olympics. (China has been exploring creating a digital currency since 2014.)

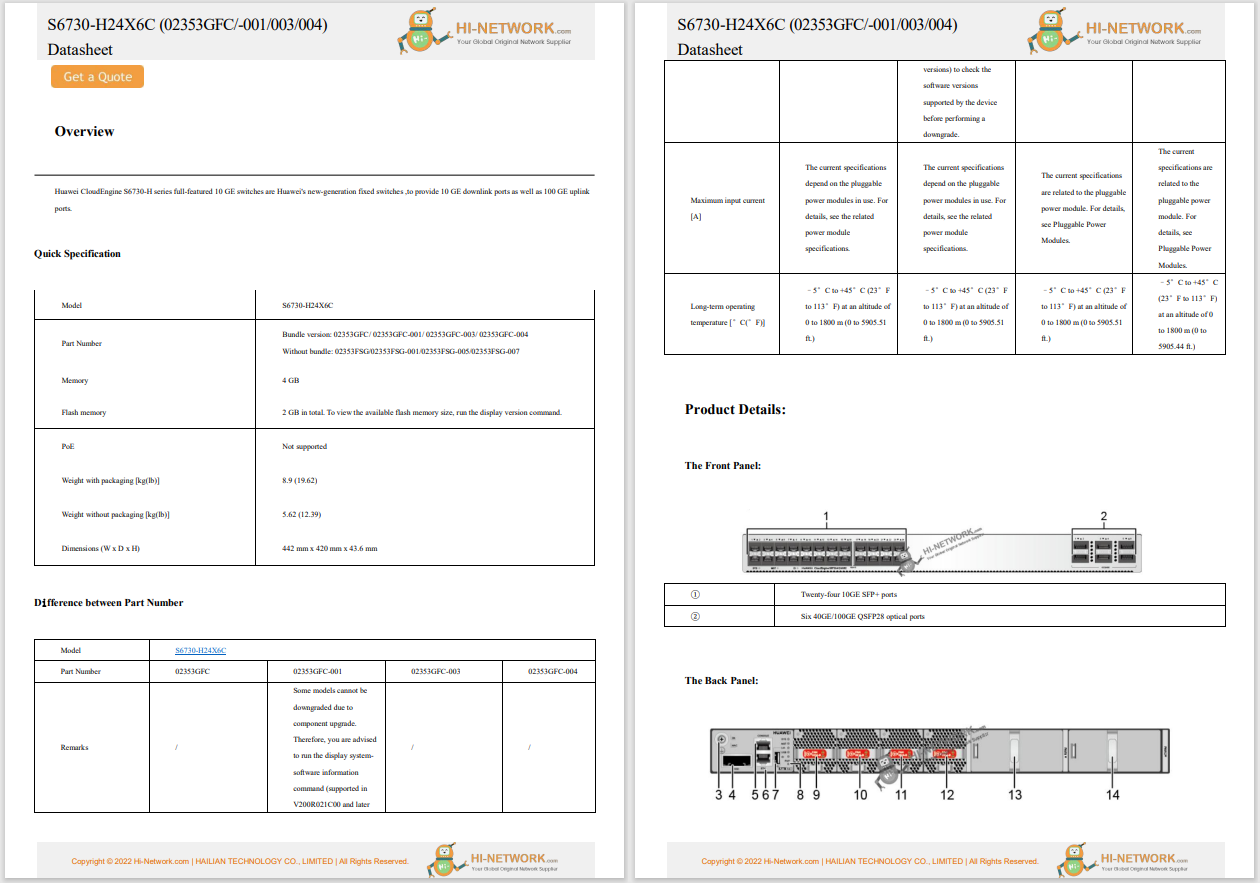

The Atlantic Council

The Atlantic Council The greener the regions, the more advanced the CBDC projects.

"Over a span of two years, the world's leading central banks have gone from skeptical to serious about a government form of digital currency," the Atlantic Council said last month.

Ananya Kumar, assistant director of digital currencies at the Atlantic Council's GeoEconomics Center, said the Asian region in general and nations such as China, Thailand and the UAE, have the most advanced CBDC projects.

For the US to actually develop and pilot its own retail CBDC - one that could be used by consumers - it would need congressional action that authorizes the Federal Reserve to move forward, "and we're nowhere near that," Kumar said.

While China's e-CNY project may be out of pilot, the billion-plus yuan transferred using over its blockchain ledger isn't as monumental as it may seem. Those transfers over the three-year life of the e-CNY rollout are only one-third of that transferred in a single day across Alibaba and Tencent Pay - China's two largest mobile payment processors. "So, comparably, it's a very small number of transactions," Kumar said.

While not yet a reality, in theory there is a threat to the US dollar because other nations developing their own CBDC networks could more easily transact without it. "We see this because there's been double the number of wholesale CBDC projects launched over the course of this year," Kumar said.

"Since the invasion of Ukraine, and sanctions packages unveiled against Russia, countries are trying to figure out what to do if that happens to them and how do they build a system against it," Kumar added.

Financial rails, or clearance and settlement systems in place today, honor sanctions imposed by NATO nations. But as CBDCs become more widely adopted, nations such as Russia, North Korea, or China could ignore those sanctions by using digital currencies not regulated by the US or its allies.

The adoption of CBDCs could eliminate billions in fees charged every year by interbank clearance and settlement systems and make the transfer of money nearly instantaneous instead taking days. They would also compete in the mobile payment space for those same reasons: backend transaction settlements.

Businesses, however, face the highest fees and longest delays when performing international payments, according to Catalini, who last year published a white paper about why the US is lagging behind other nations in developing a CBDC.

Transfers between major US banks incur fees ranging from$10 to$35 for same-day wires, and up to$3 for 2-day transactions. While the US has an interbank Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system and the Federal Reserve's FedWire, where transactions between banks happen in real time compared to batches at the end of the day, the services are limited to use within US borders. Their fees, moreover, are higher than slower, alternative payment methods such as an Automated Clearing House (ACH), creating a trade-off between cost and immediacy.

Today, international business-to-business (B2B) payments are primarily made via the SWIFT messaging network, and take between one and five business days. Settlements are also unpredictable, may incur additional fees, and vary with the number of correspondent banks involved. Incoming wire fees at major banks average around$15, while outgoing fees range from$30 to$45, depending on the number of banks involved. Processing times can also be lengthened, and fees increased by up to around 3%, if a recipient's bank requires currency conversion.

The complexity of the payment chain also makes international payments a lucrative target for business scams, since a firm's identity is not clearly linked to its banking coordinates and halting a payment is made more difficult by the number of parties involved. The FBI estimates wire payment fraud between businesses accounts for$1.8 billion in losses, more than half of it from cybercrime, according to Catalini.

"The beauty of blockchain, and cryptography in general, is it can be tailored to the problems you're trying to solve," Catalini said.

China has mostly marketed the e-CNY as a domestic effort that tests whether the country can successfully digitize cash within applications like WeChat and AliPay, two of China's leading mobile payment systems.

"That said, if you take a long-term perspective, I think it's clear [e-CNY] is a project to ensure that China will lead the way in digital financial infrastructure in the future, not only domestically but globally," Catalini said.

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is about to issue a digital currency called e-HKD for retail payments. (Hong Kong's government is considering interoperability with China's e-CNY.)

In addition to that, Hong Kong's provisional government is also considering multiple CBDC arrangements with China, Thailand, the UAE, and the BIS. Named Project mBridge, the multinational CBDC network has already settled$22 million in transactions.

"It's looking at building a corridor for settling CBDCs across all those countries," Kumar said. "I think what China is doing with its [e-CNY] is interesting. It's trying to test out how to improve adoption. So, they'll give people money in certain ways using government transfers to their accounts. They'll build in credit networks with the e-CNY."

While open and efficient because transactions in the distributed ledger technology can be seen in real time, the performance of blockchain can be problematic. That's because every entry on requires every node to process it, or come to a consensus.

Transacting off blockchain, known as "layer 2" topology, enables bidirectional processing, bypassing the distributed ledger's inefficiencies while still using its immutable properties to record completed transactions transparently.

Even before Biden's executive order, the US had been looking to create a federally-backed digital dollar through Project Hamilton, a collaboration between The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and the MIT's Digital Currency Initiative.

Project Hamilton's purpose is to create a CBDC design and gain a hands-on understanding technical challenges and opportunities. "Our primary goal was to design a core transaction processor that meets the robust speed, throughput, and fault tolerance requirements of a large retail payment system," the Project Hamilton executive summary states.

The Federal Reserve also recently published a CBDC policy paper and took public comments through May 22.

Some 80% of central banks are currently (or will soon be) engaged in CBDC work, with half looking at both wholesale and general purpose CBDCs, according to a 2020 report from the BIS.

As many as 40% of central banks have moved from conceptual research to experiments, or proofs-of-concept; another 10% have developed pilot projects.

Earlier this month, the Bank of England (BoE) asked the market for a "proof of concept" CBDC wallet. This new tender process, posted on the UK Government's Digital Marketplace, could mean a digital pound is one step closer.

The creation of such a wallet would support the BoE's work for Project Rosalind, a joint effort with the Bank of International Settlements. Rosalind's model is based on the idea that while the BoE would issue a CBDC, it would mostly be used and distributed via private organizations - per the current banking system.

"A well-designed CBDC can help provide a real-time view of risks and currency outflows to help implement specific and targeted measures to prevent financial contagions from spreading further in the event of a crisis," said Gilbert Verdian, founder and CEO of Quant, a blockchain-based financial services network.

"Many critics cite privacy and potentially overbearing government controls as barriers to implementation. They are missing that blockchain technology makes it possible to protect the privacy of individuals," Verdian added.

Avivah Litan, a vice president and distinguished analyst at research firm Gartner, said while there are solid methods to protect privacy for digital cash transactions, such as zero-knowledge proof technology (ZKP), they still rely on a central bank's good faith.

The People's Bank of China Governor Yi Gang has reportedly said that e-CNY should protect privacy, but it should not be as anonymous as cash. In October, Gang delivered a virtual speech at the Hong Kong FinTech Week conference, saying there should be "a balance between the desire for privacy and the need to prevent the currency from being used in the commission of fraud, money laundering and other illicit activities," according to Bloomberg.

CTM's Steinberg doesn't buy it. While governments today can track financial transactions, including those across international payment systems, in the US a court order is needed to access a private citizen's financial transactions. Even so, there are computer algorithms in place to flag transactions that may be nefarious, such as money laundering or sanction busting.

"People who have a privacy concern today can chose to use cash. But, we take that option away if digital cash is recorded at the individual level," Steinberg said. "That's really the privacy concern."

Going forward, there are two choices for implementing CBDCs: one enables consumers and businesses to have and maintain a bearer instrument -- to own their virtual cash by storing it in digital wallets; the other keeps the digital cash at the central bank, which accounts for who has what.

"You have a representation of your digital dollar in your digital wallet, but you don't transfer them from there. In that case the money kind of lives at the Fed. It doesn't live in your pocket," Steinberg said. "If you're building something that's the digital equivalent of cash, you can go down one route. If you're building something that's more like a like central bank version of bitcoin using a distributed ledger, you go down a different path. And, most people are going down that second path."

Tags chauds:

La sécurité

Petites et moyennes entreprises

Mobile

Secteur des Services financiers

Gouvernement ti

Tags chauds:

La sécurité

Petites et moyennes entreprises

Mobile

Secteur des Services financiers

Gouvernement ti