Image: Getty Images

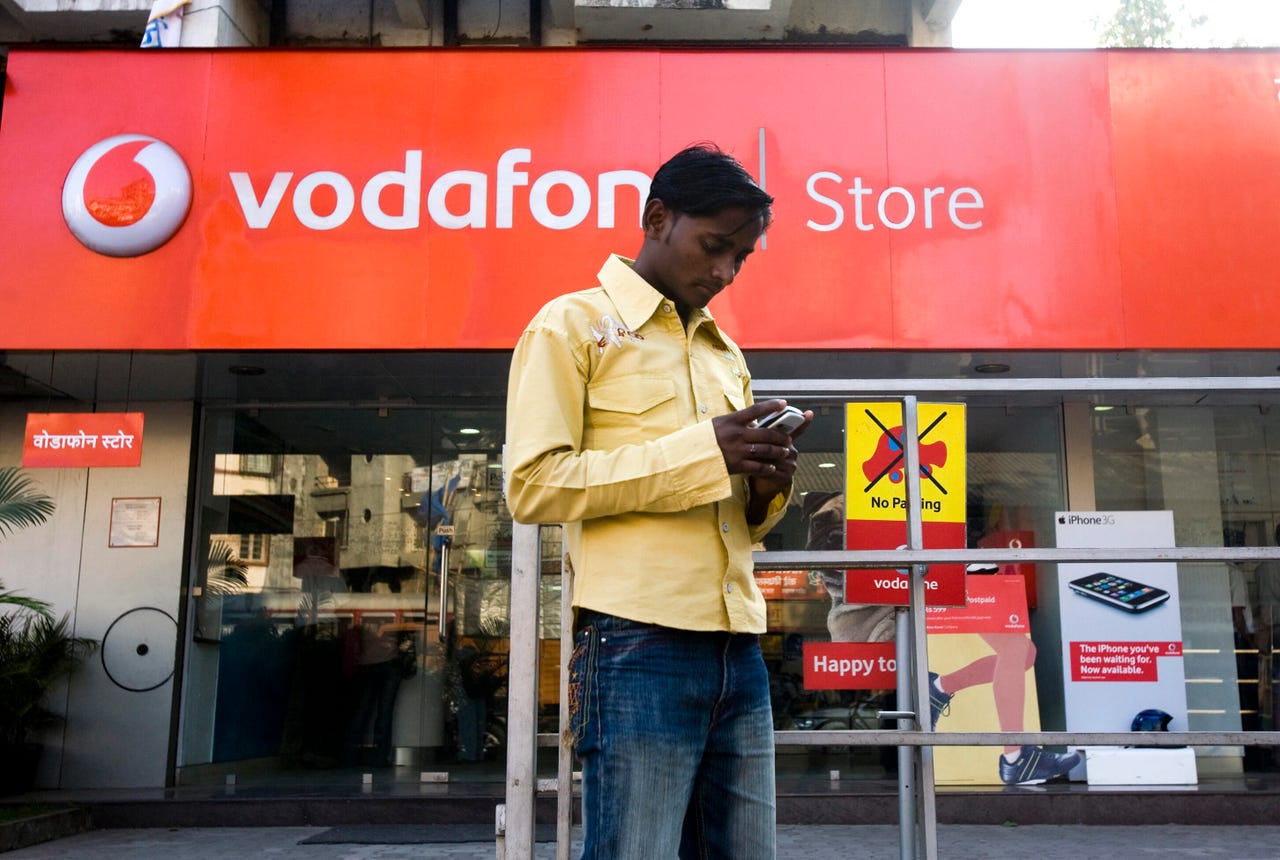

Image: Getty Images On August 5, Kumarmangalam Birla, the head of the Aditya Birla Group who has a 28% equity stake in Vodafone India, threw in the towel. He submitted his resignation from the role of Vodafone India non-executive chairman of the board.

Prospects are so bad for his company, riddled with an unimaginable amount of debt, that he is also content to hand over his stake to any entity -- government or otherwise -- that can keep the struggling company afloat.

To absorb how other-worldly that is, and the extent of its implications, not just for Indian telcos but for Indian business as a whole, consider the fact that Vodafone is not just any old struggler that is unable to manage strategy or pay its bills.

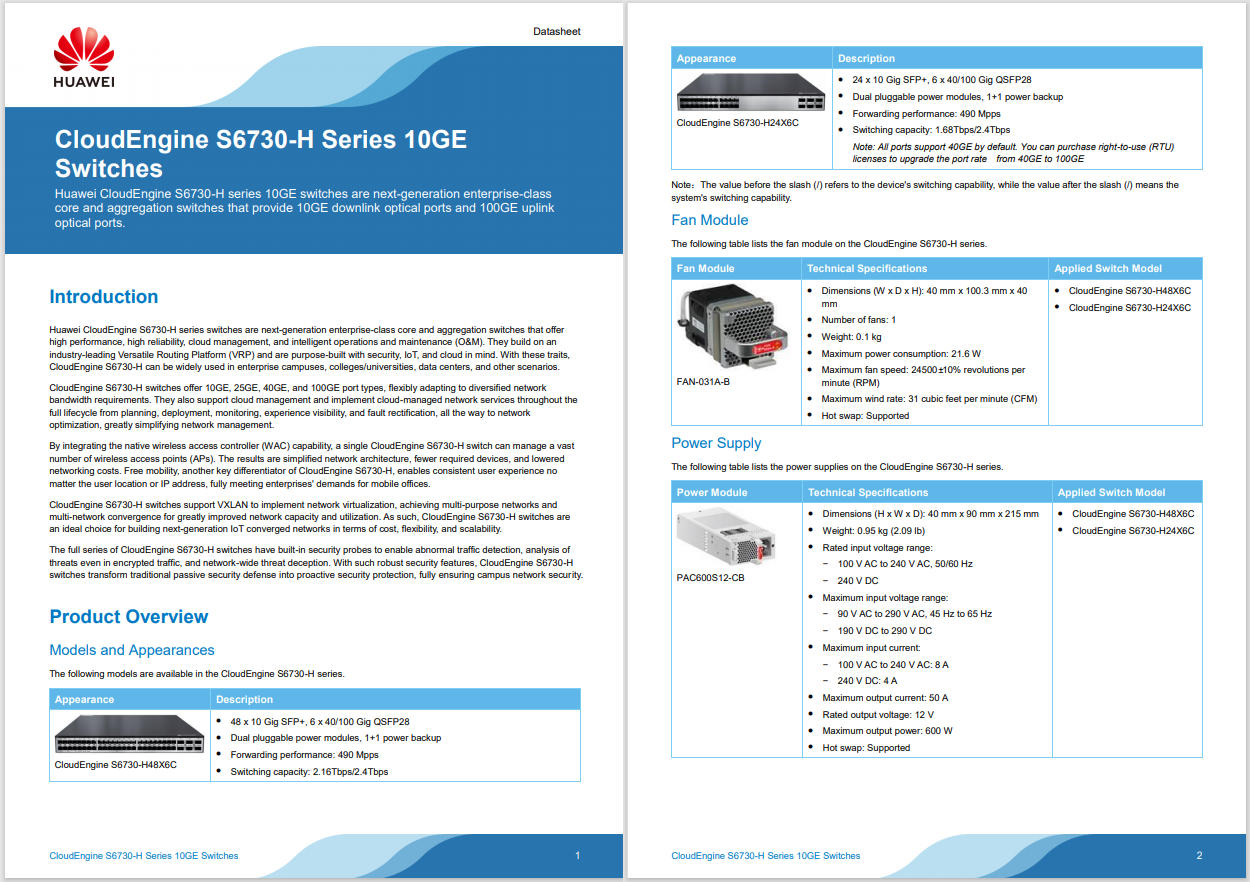

It was not so long ago that Vodafone was the largest telco in India. It now sits in third place, with 270 million subscribers -- although waves of them have decamped for competitors recently, following news of its troubles. Vodafone was reasonably well run and held its own in terms of equipment quality and service to customers.

And yet, there it lies, bloated, belly-up, and done for, unless the Indian government decides to wade in to undo the damage. Leaving aside the two shambolic, state-run telcos BSNL and MTNL, a Vodafone exit would leave the Indian market with just two bonafide players, Reliance Jio and Airtel.

In other words, a market duopoly.

Deutsche Bank AG's telco analyst Peter Milliken and associate Bei Cao have called it "the most painful market we have come across to operate a telecom".

The roots of Vodafone's demise lie squarely in two areas: the Indian government's onerous retroactive taxation policies and the mighty machine that is Reliance Jio, now India's largest telecom company.

The taxation dispute arose during the final spasms of the last Congress administration in 2012 when then Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee decided that Vodafone had withheld taxes when buying Hutchinson Whampoa's Indian ops in 2007. It didn't help that the transaction took place in the Cayman Islands, a destination of choice for tax avoidance, but to contemplate taxing something five years after it had occurred seemed brazen at a minimum.

India thus changed its laws in 2012 to retroactively ensure that Vodafone could meet its$2.2 billion tax bill. The matter went through many stages of arbitration and appeal, with mostly all of them finding in favour of Vodafone. Still, the Supreme Court of India decided in 2019 that Vodafone needed to fork over what was due.

What's more, Vodafone was ordered to pay interest -- not just on the amount due when the decision was announced in 2012 -- but on the amount accrued after the retroactive date of the 2007 transaction.

That number, owed by Vodafone, was a staggering$13 billion. It was the beginning of a road towards perdition. Its accumulated debt now stands at$24 billion, with the company posting a loss of close to$6 billion in FY21.

The other force responsible for sending Vodafone to its grave, and levelling what once was a promising sector, was the entrance of Reliance Jio.

While it is true that prior to Jio's entry, India had 12 or 13 diverse operators catering to various market segments. It's also true that Indians, prior to Jio, paid the most in the world for data and even voice calls.

In fact, it was Reliance Jio's free voice calls for life that decimated these operators almost overnight. All telecom outfits, after all, made almost all of their money from voice before the advent of cheap data, which became the finishing chokehold. Ambani's scorched earth policies were the second in a fatal one-two punch, greatly weakening other existing operators such as Airtel and Vodafone.

Reliance's ascent in such an impossibly short space of time was possible thanks to the immensely profitable oil and gas reserves business Mukesh Ambani set up. These became collateral for the$40 billion in loans that were taken out to set up Jio.

Many industry observers have also pointed to alleged governmental policy tweaking that has helped Jio gobble up subscribers and enervate rivals.Caravan Magazine has a detailed account of the murky beginnings of Jio, including its first licence acquisition. Jio has strongly denied all of these accusations.

Factor in Reliance's recent money -aising spree, ala Facebook and Google, to pay off its debt and you have a master plan to dominate the digital universe parsed in a language of national service.

Jio's late entry also meant it did not have to pay exorbitant spectrum licensing fees that other telecom companies were forced to shell out, or in most cases defer.

In other words, if the onerous demands of retroactive taxes and exorbitant spectrum did not cut Vodafone off at the knees, Reliance's predatory pricing tactics certainly did.

Today, Vodafone Idea has ?920 (crore) in cash and equivalents, and a debt that has reached ?1.9 lakh crore.

There were reports that the government convened a meeting to discuss a relief package that would mitigate or even cancel the retroactive taxes -- indeed, the government just passed a law to negate any passing of retroactive taxes moving forward.

The legislative change was seen as a nod towards architecting a plan to rescue Vodafone and Airtel, with the latter telco also owning crippling debt from the spectrum and other dues. Yet no news of a relief package has transpired over the last few days.

Meanwhile, parent company Vodafone would like to not throw good money onto struggling investments. Vodafone CEO Nick Read, in an investor conference call on July 23, said: "We as a group try to provide them as much practical support as we can, but I want to make it very clear, we are not putting any additional equity into India."

The problem is, even if the government wanted to convert all of Vodafone's dues into equity to merge Vodafone India with its government-owned carriers, BSNL or MTNL, it can't. After all, it allowed the bankruptcy of Reliance Communications -- owned by Mukesh Ambani's brother Anil Ambani -- and Airtel without making a move.

A previous telecom tribunal also stated that only after taxation payments are recovered can telcos use their spectrum as an asset to be monetised and traded. In other words, the Indian government has effectively constructed an elaborate chokehold on itself, holding a massive debt going into the billions that have largely been its own creation. That abyss will have to be financed by an exchequer if Vodafone India is forced to wind up.

Even if there were some kind of nominal reprieve, a company on its knees investing in another round of spectrum auctions and network upgrades in lieu of an impending5Glaunch is something that lies squarely in the realm of fantasy.

This isn't even taking into account the potential ripple effects of Vodafone India going bankrupt either. Vodafone rents over 180 000 towers, or 35%, of the market. If Vodafone winds up, that industry will be sent into freefall.

With some 400 million Indians yet to access the internet, the expense of the upcoming 5G upgrade looming, and a potential duopoly where one of the companies, crippled with debt, is not exactly competitive, Indian telecom is facing dark times.

Tags chauds:

Tags chauds: