The labs at Recursion's HQ in Salt Lake City.

RecursionOne way to think about artificial intelligence,in its modern deep learning form, is as a jigsaw puzzle. You have a picture on the box, and you begin to organize your pieces.

"I usually start by finding the edge pieces, matching the colors, seeing here's a white cat, say," says Chris Gibson of his approach to working on jigsaw puzzles.

Gibson is the co-founder and CEO of a nine-year-old company called Recursion Pharmaceuticals, which uses deep learning to hunt for novel therapeutic approaches to disease.

Gibson is, in fact, sorting what might be pieces to a very big puzzle.

And the picture on the box?

"The broad picture is to predict how the body reacts to anything," said Gibson in an interview withZDNetrecently via Zoom. "Any event, any drug, any protein, any molecule - what is the outcome of that interaction, and is it something that can be prevented?"

It is ultimately the puzzle of how to cure the body. "It is a big puzzle, and it is absolutely a solvable one," said Gibson. "The pieces are coming together."

Recursion, along with dozens of other young biotechs, is hoping that deep learning and other AI and big data techniques will lead to new kinds of therapies. The bet is that the AI approach will prove faster than the decade-and-a-half it typically takes to go from conception to testing to marketing drugs.

Also:The subtle art of really big data: Recursion Pharma maps the body

Recursion and the others also hope the technology may lead to a greater success rate than the industry rule that fewer than one in ten initiatives develop into a successful therapy.

Now is the moment of holding one's breath for AI in drug discovery. No company among all the AI biology hopefuls has yet brought a novel therapy to market, from start to finish, with machine learning. The world has heard a lot about the companies, and the technology, but not yet seen proof their work dramatically changes the path to solving the puzzle of biology.

"We are getting there," says Gibson of Recursion and peers' race to prove out deep learning's utility. "It is a small number of years from now, two or three," he says, before outcomes of programs in drug discovery start to demonstrate real results.

Proof that deep learning AI can solve the puzzle of disease is not decades away, says co-founder and CEO Chris Gibson. "It is a small number of years from now, two or three," he says, before outcomes of programs in drug discovery start to demonstrate real results.

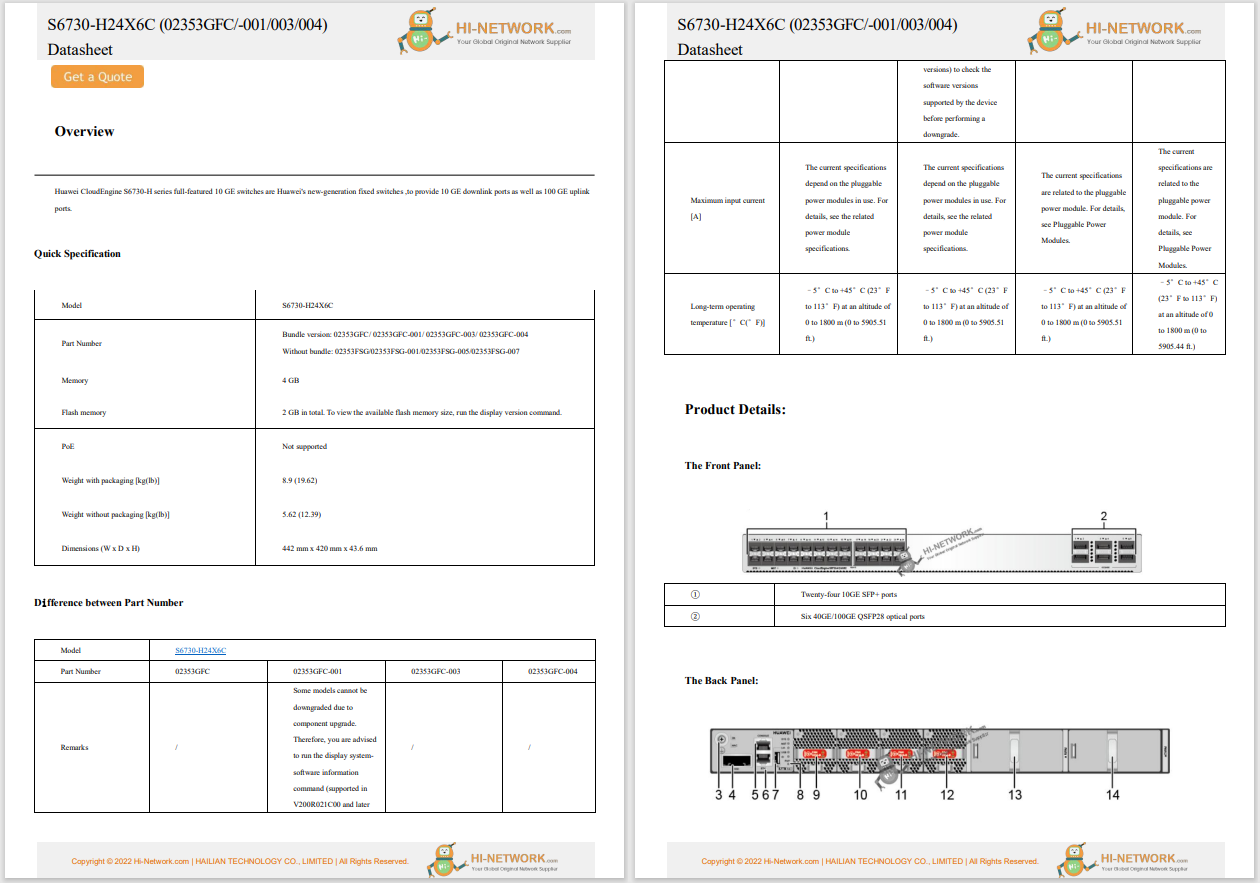

RecursionGibson's company, previously profiled by ZDNet, which went public last April, specializes in using vast amounts of data to create what are called Phenomaps, databases that contain tens of billions of relationships among various interventions carried out on cells. Machine learning technology is used to assess the significance of those interactions.

The company has amassed over thirteen petabytes worth of information in Phenomaps, and over 200 billion "inferred relationships" that can be tested in Recursion's wet lab, where perturbations can be tried outin vitroto see how a given molecule responds to a compound. The perturbations could include something like altering a cell's RNA to see how it changes the structure of the cell.

From the combination of AI-driven testing andin vitroexperiments, a substantial pipeline is emerging of drug candidates, in partnership with Big Pharma. Recursion increasingly has numerous "shots on goal," to use a Wall Street phrase, meaning, chances to find either a novel therapy or the repurposing of an existing therapy with novel outcomes, which would be just as good.

The company in January said it has upward of 50 programs, projects that Recursion has agreed to conduct with customers over multiple years, any one of which might produce a breakthrough. That is up from 37 at the time of the company's IPO in April last year.

Also:Absci and deep learning's quest for the perfect protein

Of those 50, two seem to be most immediately promising, both in the area of oncology. One is for the treatment of familial adenomatous polyposis, an inherited condition in which polyps form in the large intestine. The other is for Neurofibromatosis Type 2, where tumors form in the brain, the spinal cord, or the nerves.

Both are heading to Phase II clinical trials, when a drug is tested for efficacy, either this quarter or next quarter, according to an update the company gave earlier this month.

Gibson in January told a group of investors at a JP Morgan conference that both initiatives have shown encouraging signs. The drug for polyposis, REC-4881, showed "an almost complete reduction of all polyps." The neurofibromatosis drug, REC-2282, showed a reduction in the activation of some key pathways in patients, said Gibson, "which is pretty exciting."

Recursion has roughly 50 programs in process to either find novel cures or repurpose existing ones, many of them for so-called orphan conditions, where the population of those who suffer from a disease is fewer than a couple hundred thousand people.

RecursionRegulators, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and its European counterpart, don't yet treat deep learning forms of AI as if they are a miracle. But regulators will move more swiftly these days to remove some obstacles in drug development where there is great urgency.

When a condition is regarded as an "orphan" condition -- generally those with fewer than 200,000 sufferers, as is the case in both conditions mentioned -- the FDA and regulators in other countries will give priority to it, perhaps even waving the final, Phase III trial requirements, to get it to market when the pharmaceutical industry has passed up on trying to find a cure previously.

"Both of those are oncology indications where we have some regulatory incentive, like orphan drug designation or fast track designation," Gibson toldZDNet, referring to the FDA's way of giving priority to some treatments. "And both programs have read-outs that, theoretically, if you saw really good data, you could go to the market" without a Phase III trial.

Gibson is not predicting either effort will get permission to skip Phase III, though some on Wall Street think it is a possibility.

Gibson becomes excited about how the Phenomap can find pieces of the puzzle that were not clear with a traditional approach. In January, his company discussed how it found a gene that was not previously associated with ovarian cancer, just by using the Phenomap to work backward from a known gene that most drugs target for the condition.

Recursion works backward from maps of biology, Phenomap databases, to infer significant pathways.

RecursionWhen Recursion's scientists targeted the new gene's protein in the lab, in mice, the result was significant. "Essentially, we completely eliminated tumors, and then we stopped giving the mice drugs, and the tumors did not grow back," explained Gibson. "And that's the gold standard for an exciting oncology program."

A copy of the JP Morgan presentation on Recursion's Web site offers more details about the company's approach.

Accompanying the promising scientific results are what appear to be meaningful votes of confidence from Big Pharma. Recursion has been granted$230 million in upfront payments from firms that include Bayer AG. There is another half a billion dollars in milestone payments possible "in the intermediate term," and upward of$13 billion more potentially down the road. Then there are potential, unspecified royalties on top.

The most recent windfall for the company is a multi-year partnership with drug giant Roche and its Genentech division, announced in December. That agreement involved Roche paying Recursion$150 million up-front. In addition, the agreement comes with multiple deliverables that could play out for Recursion.

Deliverables include giving Roche and Genentech multiple Phenomaps, databases for specific oncology targets and in areas of neuroscience. Those Phenomaps can earn Recursion over a quarter-billion dollars from Roche, plus another quarter billion in additional usage fees.

In addition, forty possible programs may unfold in coming years that could each entitle Recursion to another$300 million in development and commercialization payments from Roche. That depends on each of those programs hitting their milestones.

Of course, there is no guarantee that any of the programs will meet their milestones. But should any of them make it - "if we hit it out of the park," is how Gibson phrased it toZDNet- then, on top of all those milestone payments, there would be tiered royalties that would come from Roche selling therapies.

The Roche agreement is not only the biggest deal to date for Recursion but also what seems a milestone for the entire field. "It is one of, if not the largest, non-asset discovery collaborations in pharma history," said Gibson, meaning a deal that isn't licensing an existing compound. "For no drug existing, for purely, let's go find things together, this is one of the biggest that we've been able to find, and I think that speaks to the potential of this space," said Gibson, referring to the AI-driven research wave.

Recursion has had minimal financial payoff thus far, but that is expected by Wall Street to change substantially this year. Recursion Wednesday morning announced Q4 financial results, disclosing a total of$10.2 million in revenue last year, up from$4 million in 2020. That could rise to$29 million in 2022, according to FactSet consensus.

A lot depends on the timing with which up-front payments are realized. For instance, in the case of the$150 million from Roche, although the money is in Recursion's possession, it only gets recognized as revenue as certain obligations are fulfilled by Recursion.

Also:MIT and Tsinghua scholars use DeepMind's AlphaFold approach to boost COVID-19 antibodies

"It really is recognized as we conduct the work, and my guess is just that that initial work is, kind-of, a near- intermediate-term," said Gibson of the Roche revenue, meaning, "a couple of years, three years," with the result that "it'll be recognized in chunks every quarter over that period of time."

There is a lot of pressure from investors for any young company to hit milestones to prove that financial payoff can be delivered. For the moment, getting REC-4881 and REC-2282 through the clinic is the focus, he said.

However, Gibson is already looking to the company's second phase of life, when the company organizes the puzzle pieces more profoundly. To date, finding cures has been all about taking a drug partner's existing drug and finding a better use for it, such as by identifying a novel target.

In the second phase, the company will devise novel therapies from scratch, by looking first not to what is already known, but instead to what is inferred purely from the Phenomap of a given disease.

"What I'm most excited about now is the arrival of our next generation of programs, our own chemistry, and mapping and navigating being the origin story," said Gibson.

The whole point of using deep learning, said Gibson "is to get better over time," alluding to those high, high failure rates and long, long development times in pharma. "And so if that hypothesis is true, all the programs should on average also get better over time" as they start from better insights.

"We're very excited about our first generation, we're driving them to the clinic because we believe," said Gibson. "But we think the probability of success should be increasing over time, and we hope we are going to show that these next generation of oncology programs are more transformational for patients than our first generation."

Beyond that second phase of life, there is yet another phase for Recursion, one yet undefined, said Gibson. "There are lots of things it could be," he said. It could involve testing the toxicity of a drugin silico,before any wet lab work. That might improve the number of valid targets the company goes after, for example.

"It could be that we predict some of the toxicity and absorption, and distribution and metabolism-type properties," said Gibson. Or, Recursion could go after "other modalities," he said, moving beyond just small-molecule drugs. A next phase could also involve "identifying combination therapeutics, where two drugs we predict would have a synergistic relationship against one or more targets."

When there are lots of potential directions one could go, it seems important that there is that picture of the puzzle, complete, on the box. Gibson's sense that AI can deliver breakthroughs in the coming years is reinforced because of that picture. It is a certainty that the broader whole, namely, understanding the body and curing it, will be solved with these new tools, he maintains.

"There's a lot of pressure here," said Gibson of drug development, "but it's important because whether it's us or it's somebody else that's successful, somebody is going to make a big impact here, and that's going to matter a lot for patients."

Tags chauds:

Intelligence artificielle

Innovation et Innovation

Tags chauds:

Intelligence artificielle

Innovation et Innovation